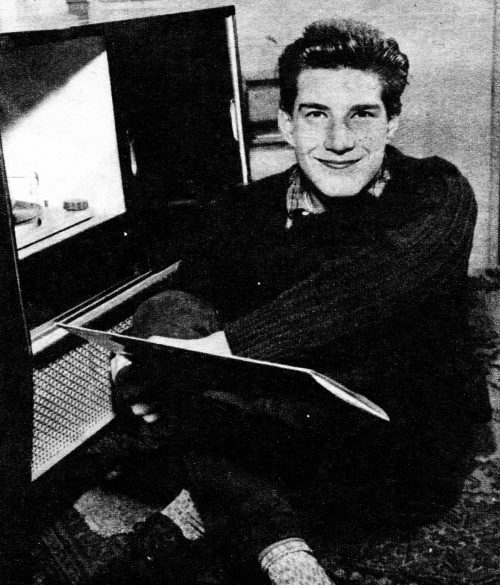

TV’s boy quiz wonder

The 13-year Junior Criss Cross Quiz champion Alan Hindle

ALAN HINDLE grinned, and shrugged his shoulders. “It’s no secret, really,” he laughed.

“Just commonsense. Ignore the subjects and stick to plain, straightforward noughts-and-crosses … and you can’t fail.”

This kind of commonsense has meant the Junior Criss Cross Quiz championship of Great Britain to young Hindle.

Fourteen soon, Alan, a technical school boy from a terrace house in a suburb of Manchester, was 10 weeks on Junior Criss Cross Quiz collecting 1,650 points — an all-time record.

He won points, not pounds. Juniors cannot play Granada’s noughts-and-crosses game for money. They score points that are later converted into prizes such as radios, typewriters, cameras, and books.

Alan “spent” his points on a record-player, tape-recorder and collapsible canoe.

If he had been playing the senior game, where filled-in squares are worth £20 [£390 in today’s money, allowing for inflation – Ed] instead of 10 points, his 1,650 score would have been £3,300 [£64,000].

That is nearly £1,000 [£19,500] more than the game’s record champion, Glasgow journalist Rushworth Fogg, won in the last Criss Cross Quiz series.

Alan Hindle played Junior Criss Cross Quiz to an almost infallible system. Almost infallible? He was eventually knocked out by … a girl challenger. I asked him if he minded revealing his success secret. “Of course not,” he replied. “Just commonsense.”

Then he repeated: “It’s easy. Look. Ignore the subject categories on the board altogether. They only confuse the whole thing. Stick to noughts-and-crosses. Play the game that way, and you can’t fail.”

Can’t fail? What, I asked, if you give a wrong answer ? Alan said: “That’s your fault. They’re very easy questions, anyway. So long as your opponent fails one or two as well, it shouldn’t make all that difference.

“You could probably get away with one wrong answer. But fail two, and I reckon that would be fatal.”

Said Alan: “Let’s suppose, for a start, that you’re the challenger. You will be, because the champion is already in the ‘X’ box. The champion has his question, gets it right and puts his ‘X’ in the bottom left-hand-corner of the board.

“Now for the all-important move. The first one. Most challengers get their first question right and then make a terrible mistake. They put their ‘O’ in a corner box. That’s wrong. The challenger’s first ‘O’ should always go in the centre. I worked these theories out with a school pal. We both applied to go on the quiz, and were waiting a year for our turn to come round. So we spent the entire year swotting up on noughts-and-crosses.

“My pal went on before me, and was knocked-out first time because he didn’t put his first ‘O’ in the middle. He went to one of the corners.”

Isn’t the centre question always the hard one? “Yes,” smiled Alan. “That’s one of the risks you’ve got to take.

“Now you’re settled into the centre square, it doesn’t much matter where the champion puts his ‘X,’ He’ll never beat you. Every move he makes, you block him. It’s as easy as that.

“Assuming you both answer your questions correctly, you must draw the game. A few drawn games, and sooner or later your opponent makes a mistake … and you’ve beaten him.”

Right, Alan. Now let us take it from the champion’s position. Into the ‘X’ box we go.

“First thing to remember here,” said Alan, “is that you’ve got the advantage from the start. You have first go at the questions, and the challenger must follow you around the board.

“The way to win is to make for the corner boxes all the time with your ‘X’s, and you’ll never be beaten. The golden rule throughout is, make the subjects take second place on the board. Play noughts-and-crosses first and foremost. I shudder when I see grown men and women getting their answers right and then throwing the game away by not playing noughts-and-crosses properly.

“Of course, crises do crop up during the game. You’ve got to be careful, and not let too many questions slip by. It’s easy to become big-headed as your points mount up, and then you do tend to become careless with the answers.”

Alan went on: “Your opponent is probably nervous. But I found that the nervous ones were the toughest fighters.

“They seemed to be all keyed-up before they went on the air, and then they fought the hardest of all. The over-confident ones were easy. They soon fluffed their answers.

“When you’re knocking up a good total, you’re faced with the difficult decision of withdrawing or carrying on. If you drop out, you run the risk of being called a coward. If you carry on, they accuse you of grasping.”

What happens to noughts-and-crosses champions when they leave school? “I’ve not decided,” said Alan. “It depends on how things go at school. Chemistry is my best subject, and I expect there’ll be plenty of openings for scientific types in the future. Plenty of time yet to think about that.”