In this Wild West town… the sheriff is 20in tall

Mosey on down to Four Feather Falls

STRIKING effects and fresh techniques making possible new strides forward in the art of puppetry are promised in Four Feather Falls, a series about a Wild West town of that name Granada presents next Thursday. Each 15-minute show is shot in the same way as a feature film, using elaborate sets and location shooting.

An electronic device — which I am told has never been used before in puppetry — ensures that the puppets’ lips are synchronised with the voices (of Kenneth Connor, Denise Bryer, Nicholas Parsons, David Graham and singer Michael Holliday).

The puppets’ wires are so thin (1/5000th of an inch [about 0.005mm – Ed]) as to be invisible on the TV screen. The sets at the studios of AP Films in Slough, Bucks, where the series was created, include a 30ft by 15ft [about 9×4.6m] prairie with trees, rocks and scrubland, and a main street of Four Feather Falls with a sheriff’s office, a saloon, a livery stable, stores and sidewalks.

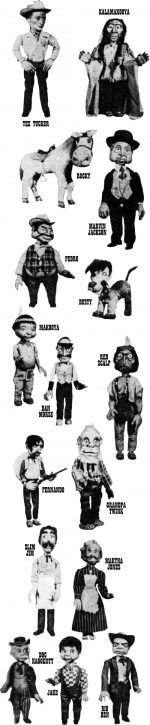

The big man of Four Feather Falls is Sheriff Tex Tucker. Tex has a simple and effective formula for dealing villains: “Git outer town and don’t ever come back.” He is helped by his horse, Rocky; his talking dog, Dusty; and his magic guns, which he will be demonstrating in the first programme on Thursday.

It is a formidable crime busting combination; life is far from peaceful, but Tex’s methods are so successful that he never has to kill a bad man, not even such desperadoes as Pedro the Bandit, Fernando and Big Ben.

Even the Injuns are friendly, up to and including Chief Kalamakooya and his little son Makooya. As for the townspeople – they are strictly in the “hearts of gold” category; notably Martha Jones, who sells candy and goods in the general store, Grandpa Twink and little Jake.

Magic abounds in Four Feather Falls – thanks to Chief Kalamakooya, who rewards Tex for saving the life of Makooya with some inside information on Indian magic. And, moving behind and above the scenes, there is a good deal of real-life “magic” of the technical kind. At an empty hotel ballroom in Slough — to the not-so-wild West of London — the creators of the series, Gerry Anderson and Arthur Provis, started making their films with just £500 [about £9,500 in today’s money, allowing for inflation] and a lot of faith.

Their team, consisting of Reg Hill (who does the model work and special effects), Jim Marsh, John Read, Sylvia Thamm (who works the robot-like electronic switch panel that synchronises the dialogue), and puppeteers Christine Glanville, Mary Turner and Roger Woodburn, works a long, tough day.

Filming starts at 8.30 in the morning and ends at 6.30. If they get more than four minutes of film “in the can” each day they consider it good going. It takes a week to shoot one episode.

Everybody has to get used to thinking small. They work in a Lilliputan world and all the props have to be specially made — no life-size articles will fit this miniature world.

Here is how the voices are synchronised: the voice “dubbers” speak their lines in a London studio where they are recorded on tape. Then, at the film studios, the tape is played back and linked, via steel strings, to magnets inside the puppets’ heads.

Sylvia Thamm works what they call a “four-channel natterer” so that at the touch of a key-switch any of four characters can be switched into circuit and the lips made to move by the electrical impulses from the sound-tape.

Everything clear? Well, never mind — just put it down to electronic magic.

Sheriff Tex Tucker needs two voices. Nicholas Parsons does the speaking and his songs are handled by Michael Holliday, who has recorded some new numbers for the series, including Phantom Rider, Two Gun Tex and the catchy theme:

“In Four Feather Falls, Four Feather Falls,

There’s always magic in the air.

But anything can happen. Anything at all …”

And it usually does.