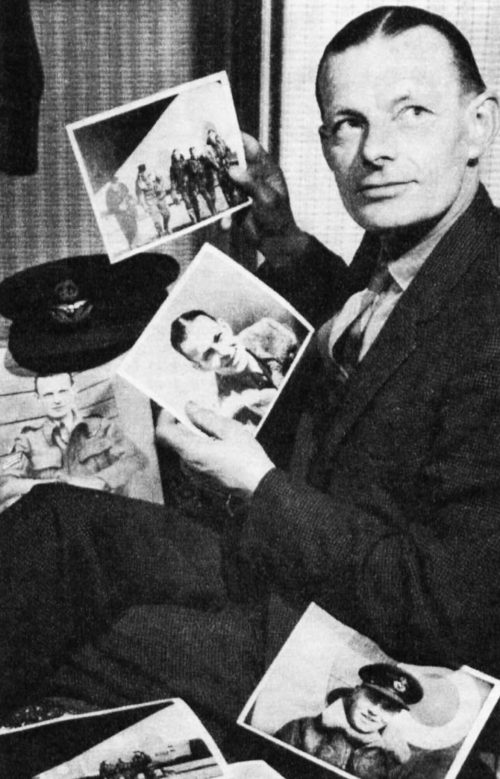

Pictures from the past

Inside the All Our Yesterdays postbag

FOR at least 10 people out of the millions of regular viewers, All Our Yesterdays will become a heartbreak programme on Monday.

Ten more widows, mothers, sisters, brothers and friends will see their loved ones wave farewell and give the thumbs-up sign in one of those cheery newsreel films of 25 years ago. Laughing troops who were later to die in action.

Every week on average, 10 people write to the All Our Yesterdays office asking for pictures of their dear departed.

Brian Inglis and producer Bill Grundy are aware of the heartbreak this weekly peep into the past can bring. They have weighed the cost and decided that this is one of the penalties that must be paid for the privilege of telling the story of Britain’s part in the Second World War.

Bill Grundy told me: “People are always writing to say I got a terrible shock last night when I saw my husband. Please try to let me have a picture of him. After that newsreel shot he was never seen again.’

“And, of course, within reason, we try to satisfy these requests. We have to confine ourselves to outstanding cases. Widows who ask for photographs of their husbands naturally get priority.

“It calls for a weekly picture hunt and a bit of detective work. We have to identify the face, track down the exact frame from thousands of feet of film, and get the picture enlarged.”

As the programme bites deeper into the war, Bill and company are preparing for more photo requests.

Going through the All Our Yesterdays postbag, I found the letters strange as well as nostalgic. A Welshman living in Oxford wrote to say that the war years were the happiest of his life.

He asked for a newsreel picture of his friends singing in the N.A.A.F.I. He wrote: “I am an invalid who has been desperately unlucky in life as a child and as a postwar adult.”

One of the most moving newsreel sequences showed a British European Forces platoon tramping through the snow in France. All Our Yesterdays received a request for pictures of every man in the platoon.

Not one of them had survived. But not one had been forgotten.

An infantryman wrote for a picture of a French farmyard near Gorre. “While I was sheltering from an air-raid,” he wrote, “a jagged chunk of shrapnel ricochettcd off the cobblestones and killed the man next to me.

“He was a Roman Catholic padre from Birkenhead. I want the picture to send to his sister.”

Often, it’s an innocent, cheery looking newsreel shot that brings the memories flooding back. Former RAF Flight Lieutenant Harold Perry, of Thornber Grove, Blackpool, saw himself and his crew clamber out of a battered bomber at Villeneuve, France.

The film was shot in March, 1940, after a typically hair-raising war incident. Mr. Perry takes up the story: “I was a wireless operator in the Whitley Mark V bomber. We had been on a fact-finding mission over Warsaw and landed by mistake at Saarbrucken, 15 kilometres behind enemy lines.

“The bullets began to fly as we tried to take off again on a very short runway. Luckily a drainage trench had been dug across the fields, and when the old Whitley hit it, we literally bounced off the ground.

“The Germans threw everything at us, but we managed to get away by some very fine ‘grass-cutting’ 3ft. above the ground.

I wrote because I am the only survivor of the crew of Old Queenie. We got back safely, but the rest of the boys were killed or reported missing on subsequent missions.”

And so the letters go on. Behind almost every incident and every face in the crowd featured in those newsreel films of 25 years ago is another story to match it in courage or sadness.