A TV service is born

Our series on the first year of Granada continues with a look at the birth of the station

THE creation of a large organization is usually a slow evolutionary process. Small beginnings are nurtured by experience, guided by precedent and enlarged by expansion or acquisition. This is true of the industrial complex, the machine of government, the voluntary organization, and the commercial enterprise. It is not true, however, of the establishment of Granada tv Network.

In May 1954, Granada Television consisted merely of a decision. This decision was that Granada Theatres should enter television, and it was taken when the Television Bill, which was to embody in statute the scope, the duties, function and methods of Independent Television, was still being debated and amended in the House of Commons. The Bill did not become law until July 1954.

In May 1955, one year later, the contract was signed which laid on Granada the responsibility for providing a weekday television service for the North of England. At this stage, apart from a contractual obligation, Granada TV consisted of little more than a general idea of what the new television service should seek to attain. There were no tools with which to carry out this idea: no studio, no electronic equipment, not a single camera; no directors, electricians, camera-men, sound and vision mixers, typists, or designers. The craftsmen, technologists, administrators and creative workers who were to create Granada Television were working at other jobs in Manchester, Toronto, London, Liverpool and New York, many of them unaware that their future lay in television.

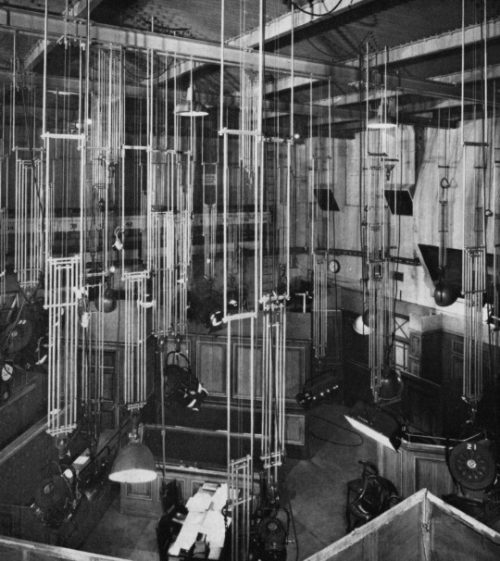

Just a year after the contract was signed, the first Granada transmission went on the air from the most modern television centre in Europe — a building which is eight months had risen on a waste plot of ground in Quay Street, Manchester, the first building in Britain expressly designed for television. It was bright, spanking and shiny new, from the electric control lighting panel to the ash-trays; from the unique lighting grid in the studio (festoons of lamps hung on telescopic battens) to the smallest valve in the master control-room.

This year of construction and creation had been hard and difficult. The Quay Street site was bought in May 1955. It was 4½ acres in size. Only half an acre was needed for the first stages of building, but the plan was to build a compact, comprehensive television centre embodying studios and workshops and offices. The first problem was to build the first section of this centre on the half-acre site, and to build it to a tight schedule during the winter months of bad weather, when it rained for days on end and the ground was churned into a muddy morass.

The first thing built was a wooden hut: in this the newly appointed Northern Administrator of Granada set up office with a secretary, a desk, and a couple of chairs. Then the skeleton of the building began to rise under the direction and drive of the building foreman, an Irishman who hustled, cajoled, and struggled to keep to the time-table despite occasional setbacks.

As the building took shape the staff grew. Instead of the hut a warehouse opposite, with 30,000 square feet of floor space, was taken over to be turned into offices. The whole building had to be gutted and rebuilt inside; at first the only offices were on the third floor, where a handful of people coped with a hundred jobs.

More formidable even than the physical problem of building were the problems of public relations: Granada TV, itself a new community, had to be established, even before opening day, as a recognized feature of Northern life; public authorities, prominent citizens of the North, and the Press had to be contacted and their support — or at least their friendly interest — secured.

The background to all this was a somewhat confused general public reaction to independent television. The new services had opened in London in September 1955, and in the Midlands in February 1956. Many viewers were eager and receptive. Some sections of the Press were hostile. Advertisers, after the first few months, had begun to approach the new medium more cautiously. Rumours were publicized about losses suffered by the companies already operating; there were newspaper criticisms of extravagance. It was assiduously suggested in some quarters that independent television was a gamble without a future. All this shook confidence, and did not make it easy to work creatively on the myriad problems of planning, building, and establishing a new service in the North. But enthusiasm grew as the organization began to take shape. Programme planning went ahead; there were difficult and even tense negotiations for the networking of programmes with the companies already operating; and actual Granada programmes were scripted, rehearsed, and tested.

Granada’s policy was, and still is, not to publish a mass of advance information about the content of new programmes. Before opening day both the Press and the advertisers were persistent in their demands to know what was being planned. Rumour and speculation spread, but Granada insisted that realization was better than anticipation, and that the new service would speak for itself and must be judged by results not blurbs.

At the same time people had to be recruited and trained. Above all, methods, drills and systems had to be worked out, tried and rehearsed; for television is an association between technology and the creative arts, dovetailed and timed to a second.

When the day’s transmission starts, there are 25,200 seconds to go before the signing-off signal; for time, in television, is measured in seconds rather than in minutes or hours. The immediacy of the medium means that the instant an image is received by the camera it is seen on the screen in the home. There is no time for revision or second thoughts. In newspaper production or moviemaking. the finished product is seen by its creator before it is seen by its consumer. In television, creator and con sumer receive an identical image at the same moment. If an actor fails his cue, five million viewers see him fail. If a scene-shifter drops a chair, millions of people hear it fall. The producers and technicians cannot say: ‘Stop. Now do it again.’

So the essence of television is pre-planning, the perfection of split-second drills so that everyone knows where he is, what he is to do, and why — and what to do in an emergency. In devising a technique and method of this fine degree of accuracy, there was relatively little experience and precedent to go by. It was not possible to create a system simply by adopting or copying rules and formulae well-tried elsewhere. So to the problem of recruitment was added that of training, and then that of coordination, of fitting the units into an effective whole.

The method followed was to decide, in outline, the various departmental responsibilities and functions, and then to engage for each department at least one expert whose job it was to recruit and train his staff and evolve the systems and methods by which they would work. The departments, roughed out in this way, were: Programming, Production, Engineering, Sales and Advertising, Film Operations, Network Operation, and Press and Publicity; managerial departments were responsible for Accounts, Personnel and General Administration. A short description of the main departments will give some idea of how a television service works; but the departments cannot be arranged in any order of priority, because each is integrally dependent on the others. It is simplest, therefore, to trace a new programme through its earlier stages.

The creative centre of a television company is its Programmme Department. Here ideas are conceived, shaped and developed into programmes by producers, directors and writers.

When a programme begins to take definite form, a period of rehearsal and experiment follows. A script is prepared and details of cast, costume, scenery, make-up and music worked out. At this stage, the Production Department adds its services to those of the Programme Planners and Directors. In co-operation with the Programme Department the Production Department is responsible for scheduling and equipping a programme for the cameras. This department organizes the construction of sets and provision of properties, wardrobe and make-up, and allocates studio space for rehearsals and final performance.

Even when a series programme is scripted, cast, clothed and rehearsed, it is still some way from transmission. Next comes a phase of assessment and appraisal. The Engineering Department transmits the programme on a closed circuit, so that it can be seen by executives as it may later be seen in millions of homes. The decisions made at this stage determine the future of the programme.

If it turns out to be altogether below standard, it will be scrapped or sent back for improvement.

If it seems right in content, casting and direction, it will be shown. This, however, is not just a matter of fixing a day and time and leaving it at that. The new programme, or series, will have to be fitted into the complex jigsaw of a programme schedule—and the details of this are arranged by another department, the Network Operations Department.

The programmes fed from the Manchester TV Centre to the transmitters at Winter Hill in Lancashire and Emley Moor in Yorkshire, come from several sources. Live broadcasts come, in the main, from the Granada Studios or from the Granada Travelling Eyes. Other live programmes come on network from the studios of other programme companies. National and international news comes from the studios of Independent Television News, a company owned collectively by all the programme companies. Local news comes from the Granada studios in Manchester. Film — which may either be a feature film, one of a series, a filmed advertisement, or an interview or exterior shot in a play or documentary — is prepared by the Film Operations Department and transmitted by the Telecine Department.

The Network Operations Department controls and co-ordinates all this material. This involves both technical and administrative work, the linking of one source with another — Granada studios with the network studios, with Telecine, and with Travelling Eye — and the preparation of precise time-tables.

The Film Operations Department is another important part of the machine. It collects the various film items from advertisers, film studios and film libraries, checks them for quality, content and length, and makes them up into continuous runs of film ready for transmission. Again, as throughout all television, timing is by the fraction of the second.

In one year this whole organization was devised, recruited, trained and set to creative work. Special training was needed in all departments. Eighty per cent of the engineers had never even been in a television studio before: they came from the workshops and assembly-lines of industry, from recording studios and from sound-broadcasting studios and control rooms. Production staff came from films, sound-radio and stage. It was not enough to tell these new-comers to follow instructions automatically. They had to learn to understand and appreciate the work of all the departments — the others as well as their own. They had to be as adaptable and flexible as the medium itself.

Studios in London, normally used for testing television equipment, were taken over by Granada for a nine-week training course which started in January 1956, fourteen weeks before the opening. Here operational studio conditions were simulated to give authenticity to training. Lectures were given on engineering and production problems. Trainees were taught the principles of lighting, scripting, designing, casting, programme-building, floor-planning, staging and the use of film and music. Then came the practical exercise: teams, each consisting of director, floor-manager and production-secretary, prepared and presented short plays, panel-games, musical programmes and interviews.

Camera-men were trained. Vision-control engineers mastered their new machinery and then studied the more personal task of making a good picture on the screen. Not one experienced microphone-operator was available: sound-crews were selected and trained to follow the sound action smoothly while keeping microphones and boom-shadows out of camera range. Vision-mixer/gramophone-operators learned their craft by constant exercise and practice.

At the end of the nine weeks, the trainees designed and produced their own original programmes and transmitted them on a closed circuit.

Meanwhile the Travelling Eye teams were being assembled and trained. Two units were designed and built for Granada. They were, in effect, studios on wheels, complete with cameras and microphones and linked to the transmitters by radio and visual lines of communication. They had also to be serviced by mobile power generators for occasions when it would not be possible to use the normal power supply.

The Travelling Eye teams were first trained in London in the techniques of handling and maintaining their equipment. After one month of this basic training they moved north to transmit ‘dummy’ outside broadcasts, from Manchester, Liverpool, Preston and Wigan, from outdoor sites and from inside buildings, practising in every sort of situation which they would be likely to meet once Granada transmission started.

On May 3, 1956, only a few weeks after the course had finished, these newly graduated trainees brought Independent Television for the first time to the people of the North.