Reporting by television

Our series on the first year of Granada looks at local news for the North

NEWSPAPERS report events after they have happened, and after the story has been written, edited and printed. But television can show the news as it happens and can project it into millions of living-rooms.

This is the story of three reports by television. Today they are something to note; tomorrow, as television develops, such reports will be a routine part of a lively television service.

On March 14, 1957, a Viscount aircraft coming in to land at Ringway Airport, Manchester, crashed on a housing estate at the end of the runway. This happened at 1.46 p.m. At 2.10 p.m., 24 minutes later, news of the crash reached the Granada TV Centre in Manchester. It was immediately decided to send out the Travelling Eyes to give a direct report of the rescue work on television screens.

Everything seemed to be against Granada’s technicians and reporters. The weather was dull and cloudy; the Travelling Eye units were dismantled and under maintenance; the crash had occurred in a Corporation housing estate on the edge of the airport, and the layout of the estate made it difficult to deploy vehicles and to obtain adequate fields of vision for cameras. The mobile telescopic aerial tower which forms part of the unit could not be raised to its full height because of the nearness to the airport. Moreover, some of the equipment and most of the members of the Travelling Eye teams were busy in the studios screening an experimental transmission of a new programme.

None the less, all resources were diverted to the story — and, in the event, Granada gave the earliest and most comprehensive reports of the crash, and also set up a new record for speed in TV reporting. Previously this record had been held by the BBC: within 9½ hours of information being received, an outside broadcast had been on the air.

This Granada broadcast was being seen by Northern viewers 7 hours after the first information had been received.

It was 2.40 p.m. when one of Granada’s research and reporting teams arrived at the scene of the crash: they saw firemen trying to clear a 20-foot-high heap of rubble and blazing wreckage; they learned that no one had been rescued from the plane or the houses into which it had crashed. Within ten minutes the story had been telephoned to Granada’s News Editor, and cine-photographers had left by car for Ringway. At the same time instructions were given to scrap the experimental programme —then ready to start — even though it was an important one and the product of many weeks of hard work.

While the Travelling Eye moved out to Ringway, Granada reporters were tape-recording reports and interviews with eye-witnesses, standing in a garden only ten yards from the wreckage. The first news-flash report was transmitted from the studios at 4.45 p.m. The programme was interrupted again at 5.18 p.m. as further dramatic news came from Ringway. At 5.45 p.m., the film taken by the Granada camera-men went out over the whole Independent Television network. Such was the speed of these events that there was no time to edit the film or to rehearse the accompanying programme of interviews and reports. The actual script, and the timing and order of the interviews, were still being worked out when the newscast went on the air.

While the newscast was being filmed and prepared, the Travelling Eye and its tender, carrying all the cables, the links-truck, the mobile telescopic aerial and the Land Rover, left the Granada TV Centre to mount the on-the-spot outside broadcast of the crash scene. As there was no time to link up with the normal electricity supply the unit took three mobile generators with it.

A producer and a director were assigned to the job; with other assistant directors they were taken straight to the scene of the crash. When they arrived they found the approaches packed with ambulances and fire-engines. The Land Rover towing the generator was lifted on to a grass verge so that clear access could be left for the fire-engines, and the other vehicles were pushed into position. Quickly the cameras were mounted on the 9-foot-high roofs of wash-houses, and cables were fitted to them from a row of houses opposite. By this time it was growing dark, so lamps were mounted to floodlight the scene. The Granada lighting equipment was functioning well before the Fire Brigade’s floodlights.

Manchester’s Fire Chief, Commander Hoare, said later: ‘Granada had some very fine floodlights which were of great assistance to us. I did not realize they were television lights until I saw the cameras. I must say the Granada electricians got them up very quickly and they were extremely efficient.’

By 6 o’clock the director ’phoned Granada to say that the cameras were working and showing pictures. But the sound engineers were meeting with considerable difficulty. Sound is normally carried by GPO line to the TV Centre, but as there was no time to lay a line, for this operation the engineers had to establish a radio link. Eventually, a sound route was established from the link-truck to Didsbury, and from there by a land-line to Granada.

At 9 o’clock it was decided to break into normal programmes in the North with the Travelling Eye report. A staff commentator interviewed two eye-witnesses and the Fire Chief, one camera using a zoom lens covering one side of the wreckage while another, at right-angles to it, covered the interviews and showed a close shot of the twisted propeller lying in front of the wreckage. A third camera, on the roof of the Travelling Eye, gave a general view. This transmission successfully completed, the Editor-in-Chief of Independent Television News was asked if he would like a further live report fed into London to follow ITN’s 10.54 p.m. bulletin. The offer was immediately accepted. Another programme was planned with a further series of interviews and more views of the wreckage and damage.

In this operation all outside broadcast records were broken. Granada reported to Britain, on the spot and while it was happening, what the newspapers could not tell until the following morning.

This was not the first demonstration of Granada’s quickness to seize such an opportunity. As early as May 7, 1956 — only three operating days after Granada had opened — another difficult technical challenge had been met.

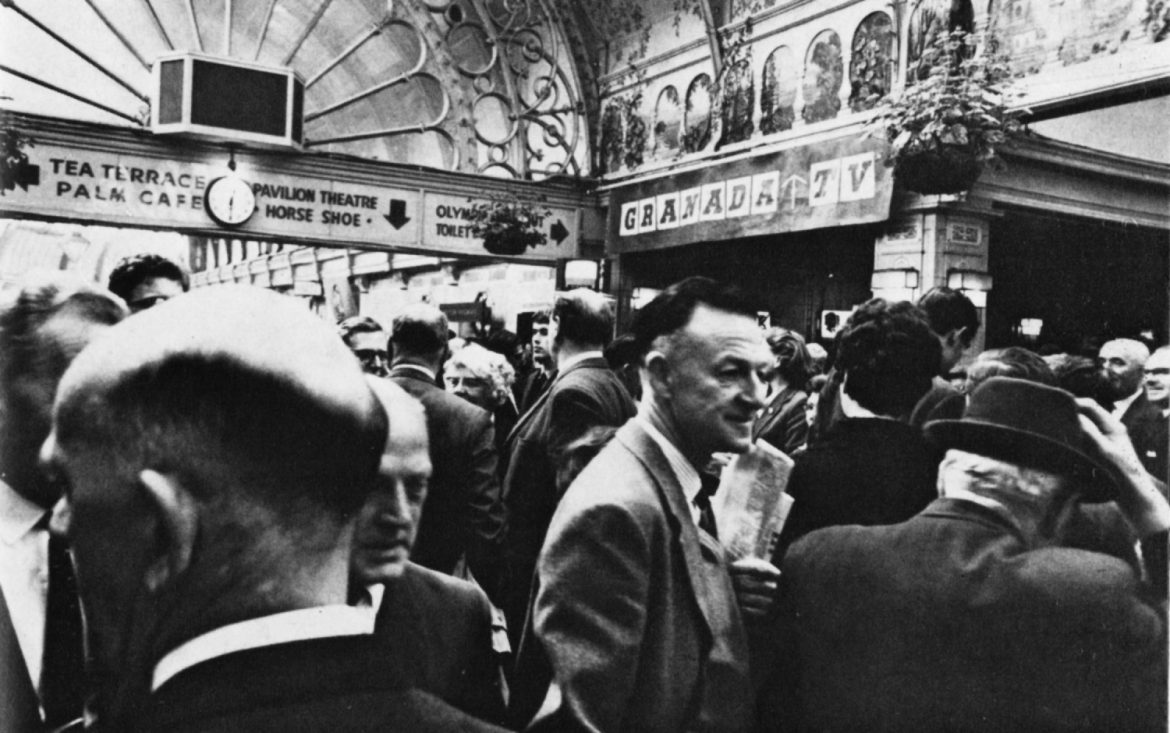

On Saturday, May 5, 1956, Manchester City won the Cup Final at Wembley. The football club and civic authorities decided on Sunday that on Monday, May 7, the team should drive in triumph from the railway station to be welcomed by the Lord Mayor on the steps of Manchester Town Hall. By mid-day on Monday it became clear that this was going to be a big news story, for the cup fever which had gripped Manchester and Lancashire showed no sign of declining after the victory. Manchester prepared a dramatic welcome for its team.

At mid-day on Monday, then — five hours and fifty minutes before the train carrying the team was due to arrive — Granada decided to report the welcome by television.

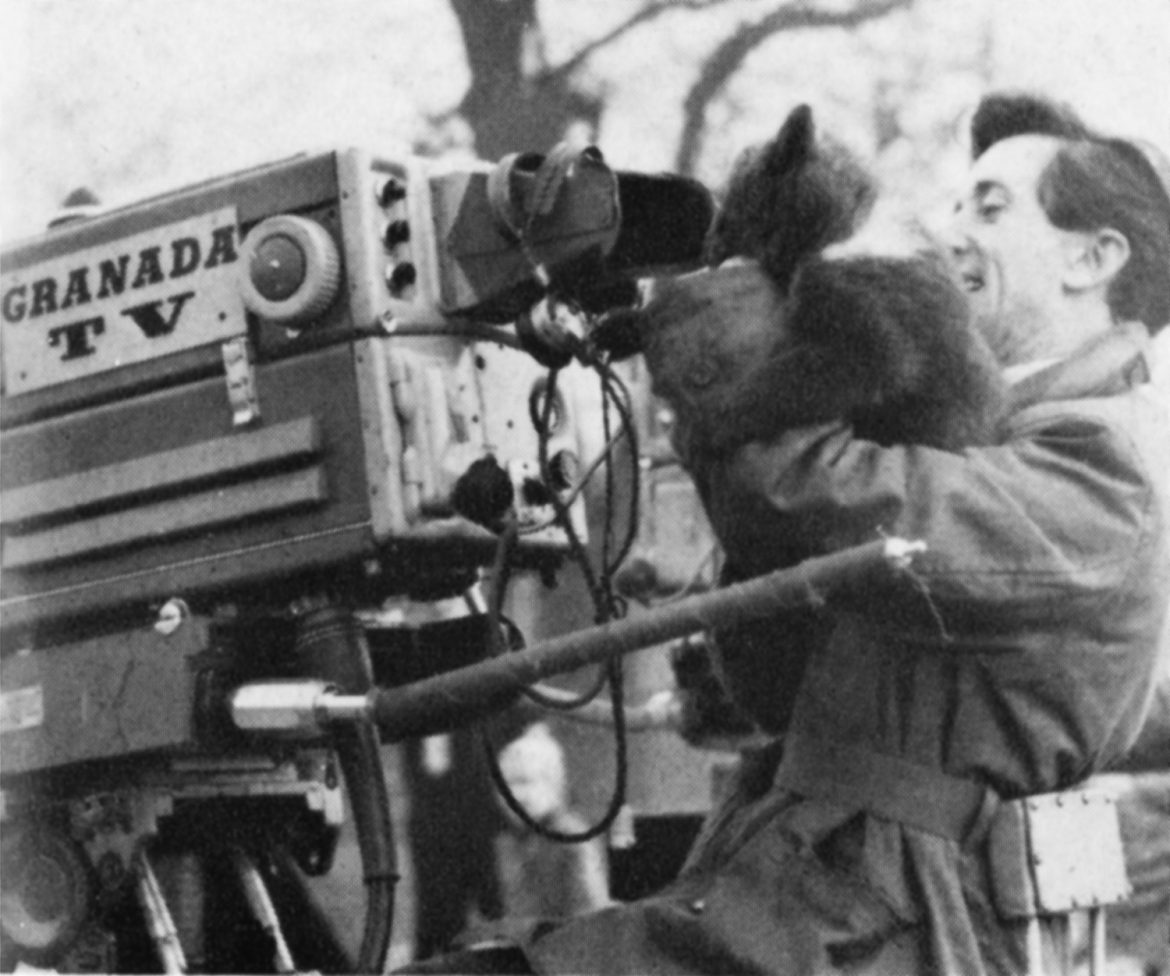

To screen a television report like this is a complex undertaking. It is no mere matter of sending a man with a notebook and a man with a camera to the scene of the story. It is a matter of moving a television studio on wheels, including three cameras, and microphones mounted in four or five vehicles. The cameras have to be mounted and rigged, GPO lines have to be booked, microphones have to be sited, all the various electronic bits and pieces have to be fitted together to send picture and sound to the transmitters. Two days’ hard work is usually needed to prepare the equipment for the transmission of a Travelling Eye programme. But the technicians of Granada, starting at noon, had to compress all this siting, rigging and testing into under three hours.

Because, in a television service, most of the equipment is in use all the time, Granada had no spare team to send to the site. One Travelling Eye team was already out at an old people’s home in Didsbury, ready to transmit a documentary programme later the same day; the other team was at Fallowfield Stadium preparing a programme for the next day.

Cameras, crews and their vehicles, sound-engineers and their microphones were withdrawn from both these programmes and told to report as quickly as possible to Albert Square, Manchester. When they arrived on the site they had to get ready for transmission, racing, as it were, against a train which had already left London. Cameras were unloaded, carried up a winding staircase, and rigged in the best available position, the window of a club which gave a view of the Square and of the road along which the coach carrying the team was to travel. Hundreds of yards of wire and cable were unrolled to connect the cameras to the transmitting van parked outside.

The next and biggest problem was to bring the sound from the Town Hall steps across sixty yards of open space, already crowded with traffic and soon to be filled with tens of thousands of football fans.

There seemed no way of bridging this gap until one of the technicians spotted a Manchester Corporation transport department line-maintenance lorry mounted with a telescopic platform. The driver agreed to elevate the platform of his lorry and carry the cable across the Square, over the tops of the buses, to a microphone in front of the Town Hall.

By 5.20 p.m., thirty minutes before the train was due to arrive, vision and sound were connected, everything was working, and clear pictures of the crowds gathering in the Square could be seen on the monitor screens.

Soon the long zoom lens was picking up a picture of the coach and the Cup as it came down the road. Another camera was showing the faces of the crowds as they cheered. Without a breakdown, without a hitch, the programme went on the air.

This kind of Travelling Eye report must inevitably be rare at the present stage of development of television. The necessary combination of circumstances — a major news story within close range of the Travelling Eye base — does not often occur.

In its first year Granada experimented with other new techniques in television reporting — for example, in the ‘Budget Day Special’, televised on April 9, 1957. In this programme Granada presented to viewers both the Chancellor’s Budget proposals and public comment upon them, all within minutes of the Chancellor’s speech in the House of Commons.

One of the Travelling Eye vans was stationed in the road between the Manchester Central Library and Manchester Town Hall. The van was in wireless contact with London and, as the Chancellor spoke, details of his Budget were passed over this link to two members of the Granada news staff sitting in the van.

They wrote the news-flashes on message forms which were then taken by runners to the garage of the Central Library. Here another member of the team cut the messages down to headlines. The caption artist then painted these on caption cards, which were mounted on a board in public view outside the Library — thus:

‘TV Licences up to £4 on August 1.’

‘Entertainments tax: Tax on live theatre and sport to be abolished.’

‘Petrol: A bob off.’

As these and other budget changes were displayed, members of the public were invited to comment on them before the Travelling Eye cameras and microphones. These impromptu interviews were then televised to the North through the Granada tv Network. Thus viewers were given not only a running commentary on the Budget, but some immediate public reactions.

Throughout the year the Travelling Eyes initiated ninety-five other outside broadcasts. In all, they provided ninety-seven hours of television — and, in doing so, travelled by car the equivalent of one-and-a-half times round the world. During the earlier months of Granada TV Network, indeed, the Travelling Eyes were actually responsible for more programme-hours from the North than all the BBC outside broadcast units together.

Viewers were shown life on a farm, a gypsy encampment and a school for deaf children; they saw people at work in a newspaper office, a fire station and a cheese factory; they saw places such as Wigan, York and the Lancashire seaside resorts. They went to horse shows, pigeon races, the Liverpool Show, and the Royal Lancashire Show.

Another series consisted of straight sports coverage — cricket between Lancashire and Australia and Lancashire and Worcestershire, baseball at Burtonwood, American football, International cycling at Fallowfield Stadium, and the football match of the year between Manchester United and Real Madrid.

A series called ‘While the City Sleeps’ showed the night-time activities of a great city — hospital, railway marshalling yards, telephone exchange, transport cafe, police headquarters, airfield, Salvation Army hostel, colliery.

The significance of these outside broadcasts is not only in their variety and scope, not only in their record-breaking speed, but in their essential contribution to the true nature of television: here indeed it is doing something which cannot be done, with comparable immediacy and impact, in any other medium.