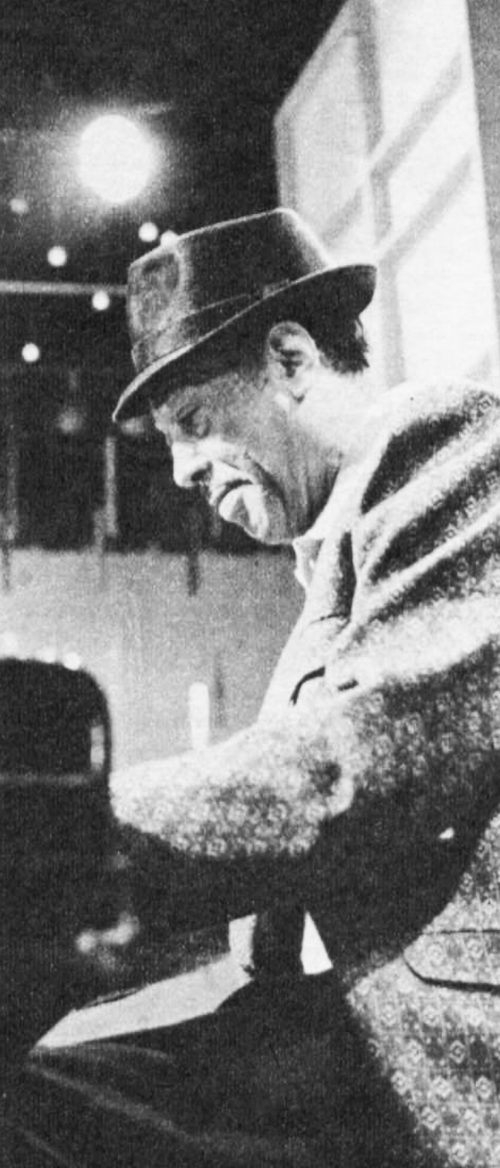

Duke Ellington

Johnny Dankworth on Granada’s latest celebrity signing

Ask a jazz lover to name his favourite jazz “giant” and he is likely to pick Duke Ellington — certainly Johnny Dankworth would. Here Britain’s top jazz orchestra leader, composer and pianist writes about America’s world-famous jazz orchestra leader, composer and pianist, who will be seen in Duke Ellington and his Orchestra on Wednesday, and says why Ellington has been such an important force in the world of jazz since the late 1920s

ALTHOUGH the name of Duke Ellington is one that most people in this country with any interest in music of any sort will have come across a great deal, it has a magic for the jazz enthusiast which is not so easy to explain.

Why, to most jazz fans, is the Ellington band far and away the most important group of jazzmen in the world today?

The answer lies obviously in the personality of its leader.

Great men break the very rules that most of us have to follow so very assiduously. And Duke has broken almost every one in the rule book which dictates the actions of the successful jazzmen.

He has been on the jazz scene now for upwards of 35 years and during that time his style has remained virtually unaltered. The ebb and flow of fashion, which exists in jazz as it does in nearly every form of self expression, has precious little effect on Ellington, who prefers to steer his own course in his very personal way.

This makes it difficult to see why those who applaud the fashionable in jazz still approve of the unchangeable Duke.

Duke also has not followed the obvious path of a bandleader by selecting the most brilliant jazz individualists of any generation and turning their virtuosity to his advantage. Many of the best-known Ellington sidemen have turned out to be quite ordinary when taken out of the framework which their mentor designed for them. And the band has never been famous for precision and dynamic range in the Count Basie sense of those terms.

The Ellington band’s unmistakable sound is largely achieved through the individuality of its leader’s writing. But even when playing rather dull music by other arrangers its identity remains.

The reason is surely that the Ellington band is a collection of soloists rather than a team. Each man will only submerge his musical personality enough to make things work.

The result is a sound which theoretically doesn’t make sense.

The saxophone section is anything but well-matched or well-balanced from the tonal or dynamic point of view, but the sound, always dominated by baritone saxist Harry Carney (of 37 years’ service), is bulbous, surging and immediately identifiable.

Of the brass the same could be said but here the special trumpet and trombone “growl” effects originated by Bubber Miley and “Tricky Sam” Nanton in the 1920s have been religiously retained by their successors.

Ellington has never presented himself as an instrumentalist leader like Benny Goodman, the Dorsey brothers, Woody Herman and so many successful jazz bandleaders have done — although he has always been technically capable of it.

The key to Duke Ellington’s success is that Duke Ellington’s instrument is his orchestra. And because over the years he has made it into a so much more expressive, adaptable and well-controlled instrument than any one man could ever make his saxophone, his trumpet or his piano, his position at the head of all jazzmen is so unchallenged today.

On meeting the man and working alongside him as I have done, it is easy to see those qualities which make his music superlative. His relaxed manner makes his 63 years seem like 40.

One could easily imagine him as a successful doctor, or even a diplomat, and certainly his gentle manner and his gift for choosing the right word at the right time would have served him well in either capacity.

Duke’s easy-going nature is apparent in his dealings with the orchestra, where discipline is almost unknown. One of the musicians once said to me: “It’s not so much like being in a band as belonging to a club.” But if the club’s rules are broken (as occasionally they are) there is no blackballing for the wrongdoer.

One Ellington orchestra-wife, who evidently admired the Duke as much as most women seem to, said to me once after two Ellingtonians arrived late on the stand: “Duke’s a great psychologist. When the guys arrive late, d’you know what he does? He don’t say nothing, not a word. And those guys feel so awful!”

So awful, I noticed, that the same thing happened the following night.

But such happenings do not reveal Ellington’s capacity for hard and arduous work at his music. He and staff arranger Billy Strayhorn often work long into the night, even after a concert, in order to prepare new scores.

Duke’s reputation for prolific output of new scores has remained undulled in spite of his advancing years. Nevertheless he tends to sleep as much as he can — some times for 12 hours at a time.

Were it not for the sheer love of his band, Ellington would certainly have given it up years ago. Likewise, some of his musicians, who could probably earn greater incomes elsewhere, stay with Duke as much for kicks as halfpence.

I once asked him why his musicians stayed so long with him (he currently has three who were with him in 1932). “Because they can afford me.” he replied.